I’ve been thinking about imagination and music, in the context of psychedelic drugs and music. Both trigger our brains in such a way as to generate a very real-feeling sort of reality, but one that is so far from reality as to be… well psychedelic.

I’ve been thinking about imagination and music, in the context of psychedelic drugs and music. Both trigger our brains in such a way as to generate a very real-feeling sort of reality, but one that is so far from reality as to be… well psychedelic.

It is of course a major incentive to find ways of exploring the possibilities of this alternative reality. It’s also equally important to devise exploration methods that do not involve drugs that create dependency or affect health – as is the case with most drugs that create desirable effects.

However we have another astonishingly powerful tool of imagination – reading. Now that everybody reads, we forget how remarkable it is.

Before reading there were story tellers who memorised the stories upon which the tribe identified itself in the universe. Then the priests took over reading – and in many cultures forbad even the rulers to learn. They knew its power, and kept it for themselves.

Today, not being able to read is regarded as grossly unusual – such that somebody must have something wrong with them if they can’t. Failed education creates massive problems in western society.

But we don’t value reading as much as we should. This is far more closely related to failing education than to the developing wonders of modern cinema and television.

In terms of powering up the imagination, reading is next in line after music – to create worlds of incredible complexity and realness.

CGI films are astonishing, but aren’t better than the imagined world of the book. You realise this as you see the film of a book you’ve read. The BBC’s recent Anna Karenina was a great disappointment to me.

Nobody’s managed to make a film of a book that’s actually more detailed with more depth than a good novel. And my theory is that probably they won’t.

Computer games have excellent sound and graphics, and are adding tactile stimulation and 3D virtual reality. It’s my opinion that this may prove a problem, as it attempts to replace imagination with actual sensory input – replicating reality in a crude fashion (compared to the subtlety with which we perceive reality).

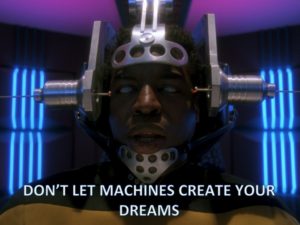

The granularity of this will of course reduce as technology improves. But the experience will remain machine-induced, and the improved detail will take over even more of the human sensorium, leaving less on which the imagination can work.

My bottom-line theory is that our brains create far better virtual realities than computers ever will, but we have to work at it. Computers stop us from making that effort.

The more our senses are stimulated, it seems to me the less we can imagine. Hearing allows us to imagine far more than seeing – or hearing and seeing combined. Hence the ability of radio drama, even from the earliest days of its development, to bring anything to life.

I suspect that hearing was critical to our survival – to avoid predators with excellent night vision. Then once we discovered the joys of rhythm and dancing, we used the imagination of hearing to make music.

We once used hearing and our imagination to keep our bodies alive. Now we have music, so that hearing and imagination can keep our souls alive.

But in the false illusion of safety in which we live these days, we have to re-learn how to listen and then to imagine. These are the essential ingredients of dreams.

For humans, above all else, are dreamers. Dreams are what got us where we are now.

And dreams are what we need for the future. Machines can’t dream – and mustn’t be allowed to dream for us.